The eighteenth century was a time of remarkable change in the medical field in Britain. This saw the development of an awareness and then action

on the huge mortality there was present in the young age group where half died in the first decade of life.

on the huge mortality there was present in the young age group where half died in the first decade of life.

|

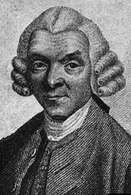

Thomas Coram

|

A social conscience gradually emerged and Thomas Coram (1668 – 1761) was the first persistent activist in stimulating the provision of care for abandoned children. He was born in Dorset and his mother died when he was three years of age. His father remarried five years later. Thomas went to sea when he was eleven years old but when he was sixteen his father had him placed as an apprentice to a shipwright. After a period in London he went initially to Boston and moved on to Taunton in the States where he established a shipbuilding firm.

In 1724 the collapse of the South Sea Company altered Coram’s plans and having retired from his position as a sea captain he was apalled by the sights he saw in London of abandoned infants and children. Coram was a married man who had no family and these appalling sights stimulated him into campaigning to improve this situation. He sought support for an institution to care for these children and from his many miles of walking to potential sponsors and backers. Ultimately he achieved his aim and after 17 years of hard and exhausting work to received Royal assent from King George II to establish the Foundling Hospital in central London. This institution, for the care and education of these deprived individuals, opened as the Foundling Hospital in 1742 and currently remains as the Coram Foundation. Although initially called the Foundling Hospital the meaning of the word hospital has changed from the eighteenth century where it was more indicative of an educational activity rather than as a treatment centre for those with illness. Coram was an outstanding achiever and his institution was at one time the favourite charity in London. Major support was given by outstanding individuals such as the musician Handel, the artist Hogarth, and other highly respected artists to assist in supporting this venture. |

|

William Hunter

|

William Hunter (1718-1783) from East Kilbride went to Glasgow University with the intention of entering the Church but subsequently changed to a medical career following a time with Dr Cullen in Hamilton. In 1741 he moved to London – took up residence with Mr (later Dr) Smelllie – at that time an apothecary in Pall Mall but Smellie became a famous obstetrician with a hospital named after him in Lanark. Hunter set up a school on anatomy which became very popular. His interests moved more to his private practice as a physician rather than a surgeon and he became a renowned in obstetrics. Queen Charlotte demanded his attention and as she had 15 children it expanded his practice considerably. Apart from his medical interests he was an assiduous collector and a careful man with his money. He ultimately gave his large collection to the University of Glasgow with a capital sum to the University for its maintenance.

|

|

John Hunter

|

John Hunter (1727-1793) might well be described as uneducated when he was in his teens as he regularly truanted from school and preferred studying nature and its wonders in the local countryside rather than orthodox lessons. He rode to London when he was 20years to join William who needed assistance in his anatomy school and John settled into this. He subsequently had training at St George’s Hospital and became an extraordinary surgeon with drive and a stimulus to broaden teaching. This was obstructed by his colleagues on the staff at St George’s. John spent all his income on material from all parts of the world for his museum which after his death was bought by the Government and gifted to the College of Surgeons where it continues as the Hunterian Museum in London. Emerging from his anatomical studies he became an outstanding surgeon but one who had difficulty in his attempts to further advance the teaching of medical students but was obstructed by his St Georges colleagues.

|

The other major change affecting the childhood population in the 18th century was the development of variolation during the century and then the widely publicised vaccination against smallpox introduced by Dr Edward Jenner at the end of the century. This stimulated the setting up of vaccination clinics such as the one established by the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons in Glasgow from 1801 which lasted most of the 19th century. The mortality from smallpox gradually fell.

return to history page

return to history page